Cloning Around

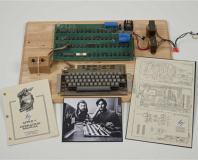

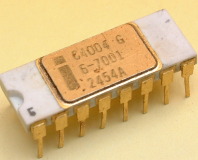

There was one crucial aspect of the PC that IBM did own, however, and that was the BIOS. As well as being responsible for controlling the hardware, the BIOS also had the ability to detect new hardware. ‘At POST time, the BIOS goes through and looks for addresses,’ explains Muldoon, 'and if it finds executable code at those addresses, it executes it and makes it part of itself. So when IBM brought out the XT, the BIOS code for the disk drive was actually on the adaptor card, so when it booted up, it saw the address of that adaptor card, executed it, made it a part of itself and then supported a hard drive.’The BIOS was an essential part of the PC, which meant that you also needed a BIOS of your own if you wanted to build a fully IBM PC-compatible clone machine. Muldoon gives the example of the software interrupts in the BIOS, including a timer tick, which was often required by IBM PC software. You couldn’t create a clone PC without a BIOS, and this presented a problem for third-party manufacturers.

These companies had two options at their disposal. They could copy IBM’s BIOS and hope that IBM didn’t notice, or they could create a ‘clean room’ BIOS from scratch that circumvented IBM’s patent.

The latter was a popular option that was employed by Compaq when it created its first Portable Computer, as well as Phoenix when it made the first mass-marketable third-party PC BIOS. ‘One group of people explains what it does,’ says Muldoon, ‘and another group of people takes that specification, don’t talk to them, and write some code to make it do that. That’s a clean room – in other words, nobody has copied IBM code, and there’s a Chinese wall between these two people.’

Muldoon notes that Phoenix did indeed create a genuine clean room BIOS from scratch, but that other clone manufacturers weren’t so diligent in their efforts. ‘Because we published the BIOS, they just copied it,’ he says. ‘Now the BIOS had bugs in it, and we knew they’d copied our BIOS because they’d copied the bugs as well.’

As IBM owned the patent on the BIOS, and it didn’t provide licences to copy it, Muldoon says the theory was that clone manufacturers with a copied BIOS owed the company money. ‘There was a whole group in the UK who went after people,’ he says, ‘and they’d knock on their door, quite politely, and say “I’m from IBM, would you tell me how many computers you’ve made, because you owe us money.”’

Keyboard Protocols

Surprisingly, you can’t just plug in a PC 5150 keyboard and expect it to work on a new PC, although it doesn’t seem as though it would be an issue. After all, the 5-pin DIN plug on the end looks identical to the connectors for AT keyboards, which can easily be plugged into a standard PS/2 port with an adaptor. However, the original IBM PC 5150 (and the later XT 5160) used different keyboard protocols from later keyboards, so they won’t work with an AT-to-PS/2 adaptor either.This compatibility issue was widely known throughout the 1980s, and many companies made switching keyboards that could be used in either XT or AT mode. However, finding one of these so that we could fire up our keyboard-less 5150 proved to be hard work, until we called keyboard manufacturer Cherry.

After all this time, Cherry still makes an XT/AT switching keyboard (called the G81-1860), so you can theoretically use it on both an IBM PC 5150 or a new PC via an adaptor. The company also very kindly loaned us a G80-1000 keyboard from its museum in Germany, so that we could get our machine working. It’s testament to the huge popularity of the original IBM PC 5150 and 5160 with businesses that, after 30 years, you can still order a keyboard for them.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.